Who was Queen Christina, and Why did she give up her crown?

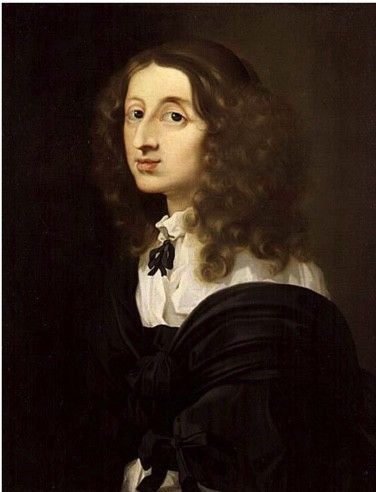

Christina of Sweden was born Kristina from the House of Vasa on December 8, 1626, in Stockholm, Sweden.

Christina of Sweden was born Kristina from the House of Vasa on December 8, 1626, in Stockholm, Sweden. Her parents were King Gustavus Adolphus Vasa of Sweden and Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg. Maria, desperate to give her husband an heir to the throne, was overjoyed when the midwives announced that she gave birth to a healthy baby boy.

As the kingdom prepared festivities for the arrival of the newborn, the midwives realized their mistake. Maria was crushed. Then she came to resent the baby girl and continued to for the rest of her life.

Contrary to his wife, King Gustavus was thrilled to have a firstborn daughter and exclaimed,

“She’ll be clever, she has made fools of us all!”

With no legitimate royal blood left to claim the throne, King Gustavus officially announced Christina as his heir. The king demanded that Christina be given a male education, so her curriculum included studies in alchemy, mathematics, religion, and philosophy.

Early in her life, Christina proved to be a bright girl, often getting praise from tutors for her intellect and quick learning of languages. With the addition of a royal education, Christina participated in activities such as hunting, which was traditionally male-dominated.

Christina was born during the height of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), a war between the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, and the Protestant regions of Germany and Sweden. In 1632, King Gustavus died in battle and left six-year-old Christina to inherit the throne.

Throughout her life and after her death, she was referred to as Queen Christina, but at her coronation in 1633, she was officially given the title of “king.”

To avoid a singular person influencing the young girl, Christina had several guardians who looked after her. This included her father’s sister, Catherine of Sweden, and his half-brother, Carl Gyllenhielm.

Due to Maria’s “hysteria” after the death of her husband, she was excluded from participating in the regency and was forced to relinquish parental rights to her daughter.

A privy council headed by chancellor Axel Oxenstierna governed the country until Christina officially came of age. Despite being educated in politics by Oxenstierna himself, Christina adopted opposing policies from her tutor. She decided to broker her treaty with the Holy Roman Emperor, The Peace of Westphalia, which ultimately ended the Thirty Years’ War in 1648.

At twenty-two years old, Christina felt the pressure of her privy council to marry so that the royal line has an heir. She quickly elected to appoint her cousin, Charles Gustavus, as her successor.

Christina is known today as possibly being queer due to her rumored relationship with one of her ladies-in-waiting, Countess Ebbe “Belle” Sparre. What is known about their relationship is that they often exchanged passionate letters and even shared a bed. Belle eventually married a man that Christina herself picked out.

As Christina grew up, she adopted a traditionally masculine gender expression, often presenting herself in men's clothing. She kept her hair unbrushed, never conforming to the meticulous grooming habits that ladies had of her time.

In her own words, Christina claimed to be,

“an ineradicable prejudice against everything that women like to talk about or do. In women’s words and occupations I showed myself to be quite incapable, and I saw no possibility of improvement in this respect”.

Throughout her reign, she maintained her patronage of the arts, earning herself the nickname “Minerva of the North” and earning Sweden the nickname “Athens of the North.” Christina wrote extensive letters to artists, philosophers, and writers from across Europe to attend her court and educate the people of her country. Her social circle turned into a Court of Learning, often engaging in deep and thought-provoking conversations.

One particular philosopher, René Descartes, had a firm influence on her. Descartes taught Christina his philosophies and became someone that she grew to respect, despite not getting along with him when they met in person at the Swedish court.

Just two years into his residence, Descartes dies of pneumonia. Christina, saddened by his death, began to ponder the decision to abdicate her throne to her cousin. Her wish was to bring enlightenment and learning to her country, but the passing of Descartes felt like a failure of that dream.

The exact reasons for Christina’s abdication are not known. Several theories suggest her decision was made due to her aversion to marriage or even converting to Catholicism in secrecy. The excuse she gave her privy council was that ruling had taken a toll on her health and that it was too much for a woman to handle (which was the most absurd and non-sensical piece of information that I came across).

With her choice finalized, Christina left Sweden in 1654. Disguised as a knight, she visited several royal courts before settling in Rome. Pope Alexander VII received her with a splendorous parade, mostly due to her publicly converting to Catholicism.

She settled there for a while and established an academy where citizens of Rome can enjoy theater, literature, and music. Across the next decades of her life, she found herself in the middle of multiple schemes, including one to take the throne of Naples (which already had a ruler) and a “trial” plus subsequent execution of her equerry¹ without justification for her actions.

Christina continued to sponsor the arts until her death on April 19th, 1689, at the age of sixty-three. She is buried at St. Peter’s Basilica, one of only three women who are buried there.

The Swedish queen left a mark in history not only because of what she did but also because of what she chose not to do. The truth of her abdication will forever lie with her, but that didn’t stop historians from speculating on her motivations, both personal and political.

Footnotes:

- equerry: a member of a royal household that tends to noble’s horses